Sei Boayue's uncle was justtrying to do the right thing.

His uncle had seen how Ebola had seeped into his beloved Ganta, a town nestled on the border of Liberia and Guinea.

The market there was teeming with people forced to purchase food every day because of a lack of refrigeration. But in the market, there is no way to tell who is infected.

So his uncle made the decision to travel there every day alone, and keep his wife, son, daughter-in-law and grandchild at home away from the risk.

It didn't work.

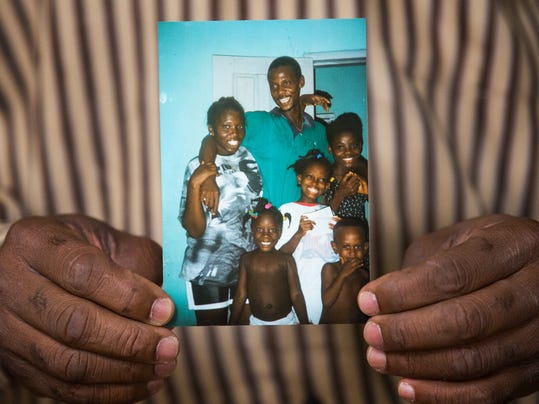

"They all passed from the virus. No one survived it. The unfortunate thing is this is now becoming a commonplace thing," Boayue, 57, of Townsend, said. "After my uncle died, you sit here and everything seems to be so daunting. You wonder: is there anything I can do?"

Boayue didn't sit for long. Just weeks after the deaths of his relatives, Boayue and other Liberians living in Delaware are fueling an effort to send as much food and supplies as they can to their remaining family and friends trying to survive in Liberia.

To date, 4,555 people in West Africa have died from the virus, 2,705 in Liberia. And those numbers continue to grow.

Boayue is working with the Delaware Community Foundation to start a charity dedicated to sending nonperishable foods abroad, a luxury for those living in the heart of the Ebola crisis.

He still has nine siblings who are living in the affected areas. He hasn't heard from one sister in over a month. There's no communication to say where she is, or even if she is alive, he said.

In Liberia, the tragedy is there is no such thing as "local" food. Traditionally, most of the food ending up on Liberians' plates has been imported, he said. After a string of civil wars over 14 years, and now the Ebola disaster, food prices have doubled and tripled.

Even if he raises enough money to buy food, copious amounts of red tape stands between his group and getting those goods on the ground to the people that need it most.

"How many kids will die within that time period," he said.

"The situation in Liberia is such that cultural attitudes also had a big part to play in the out-of-control nature of this crisis. What would help most people is food security."

Jarso Jallah Saygbe, a Liberian living and working in Dover, agreed that sanitizer and Clorox are not enough.

"The approach needs to be holistic," Jarso said. Her family living in Liberia takes each day at a time. Jarso talks to her sister almost every day and tries to send as much money and supplies as she can.

"You never know when the phone rings what's going to happen," she said.

Jarso's brother-in-law, Moses Ndama, pastor of the Freedom Christian Fellowship in Dover, held an informal meeting Wednesday evening to jump start planning for an organized donation effort for children in need abroad.

Food, clothes, rain boots and school supplies are all needed, said her husband, Moses Saygbe, who is Ndama's brother. The church is hosting a meeting Saturday at 10 a.m. to gather Delawareans from all walks of life, from West Africa to Seaford, to mobilize against the Ebola crisis.

As the planning takes off to send aid abroad, Moses said it is important for the local Liberian community to work with the state to preemptively prepare for an Ebola case in Delaware.

He'd like to see the state institute special residential centers in Delaware used to screen and house West Africans traveling into the state from the affected areas. Efforts like this would erase the stigma that every Liberian is living with Ebola, he said.

"We need to end prejudice. We are not the virus," Ndama added.

For now, the Freedom Christian Fellowship is working to send goods directly to a sister organization in the Brewerville community in Liberia.

Last weekend, the community received Clorox, hand sanitizers and soap, Ndama said. It still took a month for the goods to get there, but it's better than nothing.

They hear stories every day that are heartbreaking, but the kids are the hardest hit, Ndama said. Schools have been closed since late July. Children, many orphaned, are forced to beg on the streets and scrounge for money.

The future of Liberia rests with nurturing these children, he said.

"If we don't invest in the kids, we will lose the future generation," Ndama said.

"We can defeat Ebola, but can we survive after?"

No comments:

Post a Comment